Article

Kentucky Fried Camel; Nine Days in Jordan with Kids

Rhiannon Jenkins Tsang

“Jordan? Are you crazy? It’s not safe!” My parents were entirely happy when I told them where we were going on our family holiday.

I confess that I was just a little anxious in the days before our departure, taking our 10-year-old son, a junior pupil at school in Nottingham (UK) , into the heart of Arab world at a time of such upheaval, to a country a stone’s throw away from the horrendous war in Syria.

‘Welcome to Jordan! Thank you for coming. I am Mohammed.” Our driver recognises us immediately at Amman airport and soon our son is apparently reading Arabic.

“IKEA!” In the darkness he recognises the familiar yellow sign on the store as we speed into the capital, Amman.

“I have two sons and three daughters,” Mohammed tells us. “Jordan is a peaceful country. I thank God for it.” He lifts his head briefly towards the roof and juts his chin in the directions of the other places that do not need to be named. We don’t want it.”

It was never going to be a relaxing beach holiday, but that was what we had signed up for, an adventure. A mix up over hotels is sorted by another Mohammed and we are sipping juice in the hotel lobby in an upmarket middle-class area of Amman; the kind of place that hosts weddings night after night, but despite the faux Venetian still life paintings on the walls, leaves an impression of brown and grey. Athletes in wheelchairs and headscarves roll soundlessly around the dusty marble lobby. Para- olympic teams from Iraq, Russia, Indonesia are also here to stay.

Rome, on hills. Immediately I felt that I had been here before; a strange sensation that was to remain with me throughout my time in Jordan. It was not just the television pictures of the Middle East we have become accustomed to in recent years, but also the layers of visible history that we were to find everywhere; prehistory, iron age, bronze age, Roman, Byzantine, Umayyad, Ottoman and the modern periods. Perhaps it felt familiar because modern Jordan is part of the biblical holy lands, the lands of the crusaders and the country made famous by Lawrence of Arabia. So many of our own stories have their origins in this rugged barren land.

The black, red and green Jordanian flags tug in the still chilly breeze in front of the massive Roman amphitheatre in the centre of Amman, the new city rising around it. Our son, power walks up to the top leaving us puffing in his wake. Later in the ancient Citadel on the top of the Jebel al-Qala’a hill, the muezzins begin the call the lunch time prayer. It echoes across the buildings, from hill to hill, and I know I have crossed a great boundary between the Muslim and Christian world. Our son climbs over the temple of Hercules with the remains of a giant hand from a thirteen foot statue lying in front of it. I think of Shelley’s poem Ozimandias. He thinks Percy Jackson. Magic just the same.

Day Three brings us three other families with children who will accompany us on our adventure, and our guide, Sam, with his pony tail, Polo Ralph Lauren T shirt and grey suede shoes.

“Three cheers for the King! Hip hip horray!” In the amphitheatre someone is leading the school children in their chants. Three old soldiers in Arab military dress are playing tartan bagpipes, a legacy from the British era and no doubt now employed by the Jordanian tourist board. Suddenly Sam grabs my hand and that of my son and we are learning to dance, a slow stepping dance in a circle. People clap, cheer and join in, but not the school girls, who despite being desperate to be part of the fun, are not allowed. There are boundaries and we are beginning to see them in action.

“Kentucky fried camel”, the children decide on the menu for the evening. We pick our way along the unmade pavement down the hill to the local take away.

“Pavements run out when taxes do.” My husband explains.

Chicken, lamb, kebabs, falafel, humous, the menu is simple but good. Munching away we watch the locals pull up with toddlers on their knees in the driving seat. The neon Arabic menus are reflected in the windows against the backdrop of the white mosque over the road and I am reminded of paintings of Paris done through café windows.

Day four and we head south along the King’s Highway on our way to Petra, stopping at Mount Nebo where Moses looked into the Promised Land before he died. A group of Indian Christians are loudly sing hymns.

“Poor Moses,” say the children, “forty years in desert.” To English eyes used to myriad seas of green the arid views across to Palestine and Israel are disappointing.

“We used to run day trips to Jerusalem from Amman,” Sam sucks on his teeth, “but not these days.”

For the adults it is the morning for mosaics; the mosaic map in Greek from AD 560 found in a Greek Orthodox church in Madaba and glorious images of birds and the tree of life on Mount Nebo. We lunch in the skybar of a small hotel in Madaba, the men local men slumber on the veranda smoking water pipes. The mosque to the left, the catholic church to the right with its giant Christmas tree outside fascinates the children. The afternoon gives the children eagles soaring across great canons and the dungeons of the infamous crusader castle at Karak, built in 1142. There is no health and safety in the castle, no grids across wells and Sam throws a piece of burning tissue into the dark gloomy depths and tells of the French crusader Renauld De Chatillon who inherited the castle and interned and tortured his Muslim prisoners, throwing them off the castle walls but not before he had put a box round their head so they stayed conscious as long as possible. On the way out of Karak we pass a statue of the medieval Muslim leader Saladin riding his rearing horse in the square.

“Once a tourist thought he was St.George.” Sam chuckles. “Very embarrassing!”

Heading south again we snack on apples and almonds and Sam stops for fossil hunting on the side of the road. The whole area was once a sea and the children pick up great specimens of shells and seaweed with little effort. Another stop is made to look for rare black orchids. In the distance we hear shouts and a small crowd of little boys come belting across the field. Their socks stuffed with cardboard for shin pads and tied up with string. They love to play football.

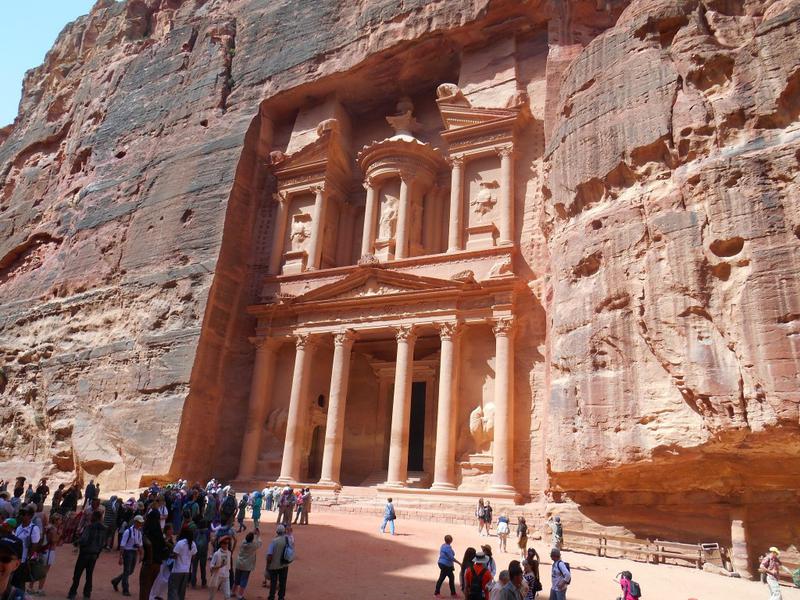

Day five has us waking up early in Petra to the sound of the muezzin in the mosque opposite the hotel who in turn wakes the cockerels. But the locals are in a good mood that morning, laughing huge belly rolling Arab laughs for someone had thrown a shoe in the face of the Prime Minister the previous day. Before we know it we are walking down the famous Siq, the narrow natural canon with towering walls that leads to the lost city of Petra and the famous Treasury as visited by Indiana Jones. The children are off, exploring the nooks and crannies, dodging the horses and carts and then we are there, standing in front of the Petra’s iconic rose stoned Treasury. But this is just the beginning. Sam is determined to make an adventure and we climb through the roofs of tombs and hike across great tranches of flat rock. There are times when you don’t need to understand a language to follow the conversation. Sam finds a scorpion for the children, which attracts the local boys who work at the site.

“Is that all you can find? What a tiddler! ” They come to Sam for play fighting and mock punches are exchanged.

“I have been guiding for twenty years. I have known all the children here since they were tiny.”

“Oye! Sam! Where have you been? I have been waiting for you all day?” A thin girl covered in black with her face veiled stands with her hands on her hips with definite attitude. She has two younger sisters with her and they are selling trinkets. Again they come to Sam for a fatherly hug.

“Happy hour!” They say. It will be happy hour all day. The elder girl is thirteen, the same age as one of the girls in our party. Sam pulls the veil away from her revealing the cheeky sun darkened face of a child with crooked teeth. Two girls from different worlds with the same needs are face to face, holding strings of coloured beads made in India.

In the afternoon we begin the long ascent to the Monastery.

“Don’t be tempted to take a donkey ride up the hill to the top,” Sam has warned. “There are cliffs and sometimes the donkeys go over the edge and the people too.” It is a steep pull. At the summit we collapse on the majilis floor cushions in a cave and drink mint tea, enjoying the views. Already the day is beginning to turn and the rocks are turning a deep red.

“Donkey ride?” the Bedouin boys ambush weary walkers at the bottom of the hill for it is another good few miles on the flat back to the Treasury and up the Siq. The children are keen, but the price is high. We set on the teenagers in the group to negotiate. The young Bedouin lean on the donkey’s saddles like a gang of pirates enjoying the sport for they know they have us over a barrel.

“That is your son? the Bedouin lad walking beside my donkey is puzzled. “But he is…”He pauses not knowing how to go on for our son is mixed race.

“My husband is from Hong Kong. But I am English.”

He nods. “Most of our visitors are English. Once there was a lady here who came and fell in love with one of us. She married and lived in a cave with her husband. But she was from New Zealand”

Marguerite Van Geldermalsen. I read her book, I Married a Bedouin. It was sad.”

“Yes. She went away to live but then came back. That is her son over there.”

My donkey begins to stall and I urge him on in the best English riding school manner. The young man nods, straightens the old donkey’s bonnet with its yellow flower and stows his whip under his arm. “This lazy donkey gives me more trouble than all the rest of my donkeys put together.” I ask him how his English is so good.

"School of life, university of hard knocks, if you want something bad enough.” He grins from under his turban, his eyes black with kohl like an Arab Jack Sparrow. We reach the Siq and the children are all safely dismounted and tips paid.“Have a lovely day!” he smiles, with the most perfect public school Home Counties intonation. Lawrence of Arabia in disguise, I wonder?

Ottoman Turks and the struggle for Arab independence. The film Lawrence of Arabia with Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif was filmed here. Clinging on, we speed out across vast tracts of desert, the rocks and cliffs rising like cathedrals out of the sand. It is a place that knows everything; every script ancient and modern already written, every face already drawn by the wind into the red desert walls. Here the rocks appear to melt like great blobs of ice cream, there they are carved into rood screens of gothic lace.

Back in the trucks we spend the afternoon exploring the desert. Sam shows the children how to wash their hands with a special local plant, we climb rocks and sand dunes and stop for the ultimate luxuries, cutting and eating a watermelon in the desert and looking at the wild spring flowers. As dusk falls the drivers put their feet on the accelerators and we race to the camp.

“YALA YALA! I think I am going to die!” The children screech with delight.

A few black goat hair Bedouin tents sit amongst the shelter of some rocks. The wood fire burns to welcome us to our home for the night. We have the place to ourselves and stretch out on the majilis round the fire to wait for the stars. The teenage children who did not know what to say to each other earlier in the week lie, crowns of their heads touching, staring up at the Milky Way. Sam has a constellation app on his phone and the younger children busy themselves with it, but this night I prefer to enjoy the glories without giving them a name. We feast on mezzes and barbeque. The fire cracks and Sam brings out a large bag of marsh mallows for the children. Now there are only shadows and voices. An Arab man comes to sit smoke by the fire and a couple disappear into the desert night. We pour wine and brandy into paper cups so as not to put alcohol in the Bedouin glasses. The children begin to sing “Dumb ways to Die,” a funny song off an ipad’ and then I hear the unbroken voice of my son singing alone, a hymn from school. “I am here Lord, can you hear me!” I know that in this darkness he is neither shy nor afraid.

© Moronic Ox Literary Journal - Escape Media Publishers / Open Books

Moronic Ox Literary and Cultural Journal - Escape Media Publishers / Open Books Advertise your book, CD, or cause in the 'Ox'

Novel Excerpts, Short Stories, Poetry, Multimedia, Current Affairs, Book Reviews, Photo Essays, Visual Arts Submissions

About the author:

Rhiannon Jenkins Tsang was born and educated in Yorkshire. As a young person she spent a lot of time in Europe, and speaks French, German and Spanish, as well as Mandarin Chinese and Cantonese. She read Chinese at Oxford and made her first trip to China, via Karachi and Islamabad, at the age of nineteen. She found a silent, black and white country largely abandoned since 1949, and a traumatised people emerging from the Maoist years, bravely hoping for better things.

She has worked in business in the UK and Taiwan and is a non practising lawyer. She runs Chinese language and cultural training courses for businesses with China links.

Rhiannon has worked as a freelance writer in Taiwan and was a runner up in the Woman and Home magazine short story competition. She has also had a short story about being an English mother with a baby in Taiwan, broadcast on BBC Radio Oxford.

She lives a traditional Nottinghamshire village with her husband, Steve Tsang, and their nine year old son. When not writing, doing school runs, or otherwise mothering, she enjoys walking, yoga, tennis and watching cricket.

About the Book...

It is 1949 and the Chinese

Republic is collapsing under Mao Tse Tung’s communist onslaught. Manying,

distressed and frightened and unsure of the fate of her soldier husband, must

flee Nanjing with her baby. With the help of her beloved childhood sweetheart,

she finds a place on the last train leaving the city and endures a horrifying

journey to Hong Kong where she is taken in by her brother and sister-in law.

Grief-stricken and destitute, she struggles to make sense of the world in which

she now finds herself. As she recalls the cruel fate of her uncle at a

provincial court half a century earlier and all that has been lost, she makes a

discovery: the past shapes the present. Fate, however, has yet more in store

for her. Love, war, sacrifice, corruption and revenge all play their part in

this epic story that reaches its climax in twenty-first century Shanghai.

More Open Books titles for your enjoyment

“Mummy,” my son is clingy in the strange room with Arab music coming from the TV, and I stroke head until he falls asleep, carefully unplugging the the switch with loose wires hanging from his bedside lamp.

Day Two and we launch ourselves into downtown Amman, armed with the hotel’s card with its address in Arabic, and stern warnings from the porters to make sure taxi drivers put their metres on and not to pay more than three and a half dinar for our fifteen minute drive into town. Amman is an ancient city built, not unlike

“Complaints; I can do nothing about,” he says, "Problems; I can solve. And remember, in Jordan there are no prices. Everything is to be bargained for. Yala!” And we are off, heading north to the Roman city of Jerash.

You have to hand it to the Romans, they knew how to build a city. The templates are the same from one corner of the Roman Empire to the next; forum, baths, amphitheatre, streets, shops, fountains, and beautiful drains. But Jerash was different from the many Roman ruins we had climbed over on European holidays. Buried by sand for generations it has been rediscovered relatively recently and was huge and comparatively intact. The Hadrian’s Gate had been restored, columns still stood and there were Roman sleeping policemen in the roads to stop the carts racing.

Sam is scrabbling in the dust picking up something small, and soon the children are following his lead, collecting loose pieces of Roman mosaic lying loose all over, for anyone to find.

The girls are coming up to us, parties of girls on school trips with red roses in their headscarves or bonnets against the sun.

“I want to be a tour guide. I want to be a teacher.” They offer us almonds from their brown paper penny packets. But where are the boys?

“It is girls’ day, “says Sam. “It is better for us. The boys are not so polite.”

Back at the hotel the children splash in the pool unaware of the issues facing their mothers. It is a locally run hotel and there are no men and women’s times but equally there are no changing rooms for women. The changing room is mixed. The message is clear. I sit in the shade. The young men pump iron in the gym whilst the older men stop for afternoon prayer, in the corner of the room where three prayer mats have been laid out in the direction of Mecca.

Day six and I watch my son eating his lunch of “upside down chicken with rice” in a Bedouin tenton the edge of the desert at Wadi Rum. Happy with his new friends, the children just take everything in their stride; language, food, watching Wolverine with Arabic subtitles last night after our Petra trek, and with boundless energy throwing themselves into the swimming pools at every opportunity. After lunch we pile into the back of pick-up trucks and head out into Wadi Rum, a place made famous by the English maverick TE Lawrence and Prince Faisel’s 1917 campaign against the

“Stop here! All out for tea! ” We have not been driving long when we pull up at some Bedouin tents for mint tea. I decide I can cope with the desert if there is to be tea. Our drivers are having a heated conversation in the corner of the tent but Sam is there arms out to the side, palms raised, mollifying, haggling, persuading as he does throughout our trip, keeping us safe.

“Habibi! My friend!” Frowns turn to smiles, kisses and an embrace.

“Stop here! All out for tea! ” We have not been driving long when we pull up at some Bedouin tents for mint tea. I decide I can cope with the desert if there is to be tea. Our drivers are having a heated conversation in the corner of the tent but Sam is there arms out to the side, palms raised, mollifying, haggling, persuading as he does throughout our trip, keeping us safe.

“Habibi! My friend!” Frowns turn to smiles, kisses and an embrace.

The morning of day seven brings a camp fire breakfast and a couple of Bedouin likely lads with a train of camels for our return trek. They take care to match the child to the camel putting the smaller children at the front and back of the lines. Wise, I learn, for the camels in the middle tend to bunch and bang up against each other crushing the rider’s legs if he is not careful. Suitably mounted we set out across the desert with our guides. The children are the quickest to adapt to the sea rolling gait and strange saddles. It takes me a few minutes to realise that a camel is not a horse and I find it easier to ride with one leg over the pummel. The children are busy naming the camels, Fish Lips and Dozy, while I soak up the last minutes of desert serenity and awe.

Leaving the desert we head south to the port and resort city of Aquaba, following in the footsteps of Lawrence and Faisal along the Turkish railway line. Bizarrely, an old steam and diesel engine and a couple of carriages from the old railway have been left in a siding. We stop to explore. In touch with their inner child after a night camping, the Dad’s climb onto the carriage roof tops and run along the top leaving us mothers to restrain the children.

“Do as you father says, not as he does!”

It is Good Friday and Aquaba is heaving. Everyone, Jew, Muslim, Christian is on holiday. We take a glass bottomed boat out into the Red Sea looking at the corals and an old wreck. The strategic significance of the location is immediately apparent, for in this corner of the world Jordan, Israel, Egypt and Saudi Arabia bump up against one another. After lunch we dive off the back of the boat to snorkel. I wondered what the Arab Israel ladies on the top deck in their headscarves and long abeyya coats thought of us all.

Day eight takes us north through areas of desert and oasis to the Dead Sea. Sam talks of the biblical dens of iniquity, Sodom and Gomorrah, which some archaeologists think might have been on the southern shore of the Dead Sea. It is a pitiless wilderness of grey rock and quick sand. We pass Lot’s wife on the top of a hill, who looked back and was turned into a pillar of salt. Arriving at The Holiday Inn Dead Sea Resort, I think that perhaps it is five star hotels that are the new promised lands; acres of swimming pools in a country with a dire water shortage, American managed, staffed by Filipinos with pizza and ice cream on demand and wifi that works. The children certainly are in heaven! A close knit group after all the adventures they spend hours in the pools. Finally we persuade them down to the shoreline. A strange experience, for the there are no real waves in the Dead Sea, the water is too viscous, and there are no fish and no seagulls, just heat and silence. When you try to swim on your front the water pushes you up so you are left with your legs flapping in the air mermaid style. Giggling, we coat each other in thick black mud and stand Maori warrior style on the shore to bake and dry.

Day nine is Easter Day. Hotel staff dressed as bunnies hand out eggs, but none of them seem to know what Easter is. Passing the baby pool, Barney the purple American dinosaur, invites you to waggle your ears like a rabbit. I turn down a chance to visit Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Al-Maghtas) the site on the river Jordan where John the Baptist is supposed to have baptised Jesus. Sam has told me that the river is just like a stream and I do not want to spoil the visions implanted in my head since I was a child of a broad river with a green meadow full daisies and poppies on the far side;

“I looked over Jordan and what did I see? A band of angels coming for to carry me home…”

In the evening as the sunsets over Jerusalem in the West we take our last meal together.

“What was the best thing about Jordan?” we ask the children.

“The eagles, the scorpions, the dungeons, the camels! Everything!”

But I know, like Lawrence of Arabia, I have left a good bit of my heart in the cathedral of the stars that is Wadi Rum.

Rhiannon Jenkins Tsang is writer based in Nottingham, author of the novel The Woman The Woman Who Lost China CoverWho Lost China and member of Nottingham Writers’ Studio. www.rhiannonjenkinstsang.com

Self funding, Rhiannon travelled with The Adventure Company.

The tour consultant was Jude Plant at Trailfinders, Nottingham.

The freelance guide in Jordan was Osamah Salamh Twal (Sam) : osamahstwal@hotmail.com

Photography Andrew Johnston and Osamah Twal.

Click ad to buy at amazon.co.uk